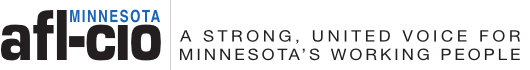

Union members are becoming increasingly scarce in the U.S. labor force. It’s a trend that continued in 2016, when union density fell from 11.1 to 10.7 percent of the total workforce, according to federal report issued in January.

Unions’ demise has assumed an aura of inevitability. So when the Bureau of Labor Statistics released its annual report on unions, media outlets mostly yawned. The headline – “Union membership dips to lowest point in recent history” – showed up in the cable-news crawl, as a one-off tweet or buried inside the Business section.

Four days later the nonpartisan Pew Research Center released results of a different survey, showing more Americans – roughly six in 10 adults – view unions favorably than at any time in the last 15 years. Young people, in particular, hold favorable views of unions – three-quarters of those ages 18 to 29, according to the Pew report.

How can union membership be declining while unions’ popularity is surging? Why aren’t more people forming unions?

Labor experts and union organizers say the seemingly contradictory trends illuminate just how challenging the process of organizing unions is, particularly in an economy that looks little like it did when U.S. labor laws were drafted 80 years ago. But experts also say the numbers don’t reflect non-traditional organizing campaigns that have picked up in recent years, many of which are yielding improvements for working people and, more broadly, helping the labor movement stay relevant.

“I feel like we’re at a moment of pretty dramatic change where there needs to be a different model, a different way of doing things,” Monica Bielski Boris, director of the University of Minnesota’s Labor Education Service, said. “Unions were a pretty important part of changes that led to our current (labor laws) in the 1930s, and I’m hopeful they will also be an important part of that happening again.”

People like unions!

Pew’s survey results, which showed a remarkable, 12-point uptick in unions’ favorable rating in less than two years, don’t surprise Cat Salonek, who has worked 10 years as a union organizer, now locally with the Communications Workers of America and the Newspaper Guild.

Being slighted or disrespected at work, she said, is a near-universal experience among working people, and most of the time they feel powerless to do anything about it. Unions appeal as a way to take power back from their bosses.

“The No. 1 reason people want to form a union is dignity and respect in the workplace,” Salonek said. “You might think it would be pay – and it’s a close second – but the No. 1 reason is they’re sick and tired of being sick and tired. Most people really want a union because they’re being treated so badly.”

The petty grievances have a way of adding up, Salonek explained. One group of workers reached out to her after management, responding to their repeated requests for a water cooler, finally gave in, but refused to provide cups. Another group decided to organize after their boss removed the break-room table. “They were so outraged they drew a chalk outline on the carpet of the floor where the table used to be,” she said.

Retail and health care workers approach St. Paul-based United Food and Commercial Workers Local 1189 with concerns about unpredictable schedules and paid time off, organizing director Abraham Wangnoo said. “People with young families want to be able to see their kids’ sporting events, to plan their lives.”

That’s not to say rising income inequality and corporate power aren’t behind renewed interest in unions, too. Young workers were particularly “drawn into that analysis of corporate power and wealth” put forth by Bernie Sanders’ presidential campaign, Bielski Boris said. “Unions were seen as part of a solution to deal with those problems.”

“They realize not every person is going to be the CEO of a company,” Wangnoo said of young workers. “They have to stick together.”

Broken system

Perception isn’t the problem unions face, organizers and experts say. A broken system is.

In 2011, after their repeated requests for paid sick days fell on deaf ears, workers at several Jimmy John’s sub shops in the Twin Cities decided to unionize. Their scrappy, upstart effort drew enough support to prompt the National Labor Relations Board to conduct an historic union election in the union-free world of fast food.

The franchisee, MikLin Enterprises, responded with a campaign intended to scare its 170 employees from supporting the union. MikLin fired six workers active in the campaign, a move that sapped momentum from the organizing drive. Workers voted 87-85 against a union.

The six workers filed complaints with the NLRB, arguing MikLin had fired them in retaliation for exercising their legally protected right to engage in union activity. One year later, an administrative law judge sided with the workers, but MikLin filed the first of a series of appeals that ended, finally, five years after the organizing election, when a federal appeals court ordered the six workers reinstated to their former jobs.

But by that time, as documented in a Huffington Post report, all six workers had long since moved on to new careers, from computer programming to teaching. The idea of going back to fast-food work was laughable, but it laid bare the challenge working people face when they organize a union.

“Not only is the process very cumbersome, the penalty for employers who engage in bad behavior during an election, including firing people, has never been very real,” Bielski Boris said.

What happens after an employer gets wind of union organizing in their shop?

“They hold one-on-one intimidation sessions, use coworkers to apply pressure, spread misinformation about strikes, about dues,” Wangnoo said. “It is hard to imagine, to understand the pressure it puts on somebody who has kids and a life they want to live and bills they have to pay. It’s terrifying.”

Dwindling resources

Unions’ high favorability rating is playing out in NLRB elections nationwide, which unions won at a rate of about 70 percent from Oct. 1, 2015, through December 2016. But the very number of organizing elections taking place – just over 100 per month across the country during that span – illustrates how hard it is for workers to rally enough support to call for a vote. (Most organizing elections are held by the NLRB, but not all. Public-sector elections in Minnesota, for example, are conducted by the Bureau of Mediation Services.)

Employers’ sophisticated, anti-union campaigns are one reason organizing drives don’t often reach the threshold for an NLRB election. Another, Bielski Boris said, is the level of resources it takes to conduct an organizing drive – resources unions are finding increasingly scarce.

Outsourcing and automation, Bielski Boris said, have decimated sectors of the economy, namely manufacturing, rich with union density. Shrinking membership, combined with anti-worker “Right to Work” laws, have forced many unions to choose between responding to workers who want to organize and providing service to existing members.

“It’s incredibly expensive for unions to organize,” Bielski Boris said. “The process is so arduous that even unions who want to organize have some trepidation.”

A changing economy, a new organizing model

Ironically, while working people crave the stability and security a union contract provides, the economic forces at play in destabilizing the workplace are, themselves, barriers to organizing unions.

As more workers settle for short-term gigs – think Uber and Lyft – rather than work in traditional shops, many find themselves labeled as independent contractors rather than employees. And labor law says working people must share a common employer in order to join together in a union.

Salonek, who works with language interpreters and ESL teachers, said independent contractor status “voids those workers from NLRA rights.” If they want to unionize, they must first get reclassified as employees, “and then the employer knows you want a union before you even start an organizing campaign.”

In response, CWA and other unions are exploring alternative union structures that reflect the way working people built power before the NLRA, Salonek said, including professional associations and guilds that advocate for workers in a specific industry. The throwback model comes with several challenges, though. Laws that prohibit price fixing prevent workers’ associations from setting wage floors, for example.

Unions also are exploring new benefits to membership that might attract independent contractors, freelancers and, in Right to Work states, dues payers. They include health insurance plans for workers who bounce from gig to gig, malpractice insurance, professional development and more.

Building Trades unions offer a glimpse of how unions might enhance their appeal to “gig-economy” workers. “You belong to a union and it helps you train for employment and connect with employers, and it sets some baseline standards in the industry,” Bielski Boris said. “They offer a model where transitional employment is built into the DNA of how they operate.”

Reports of unions’ demise as a share of the workforce also fail to reflect successful organizing taking place outside of traditional collective bargaining, including the Fight for 15 and expansion of worker centers.

In the Twin Cities, the worker center CTUL has given retail janitors and fast-food workers a collective voice on the job. Last year, CTUL’s organizing effort resulted in a new union of workers in an industry – retail cleaning – rife with wage theft, as temp agencies and subcontractors cut corners to provide big-box chains with the lowest bid.

The historic victory provides a glimmer of hope for Bielski Boris that unions might restore more than their Pew survey numbers.

“This is an opportunity to figure out what’s possible for labor,” she said. “If working people can see the value unions play in challenging the system, there’s some hope. But if we allow grief to take hold, we’re most certainly going to end up with the results we fear most.”